O3b Networks, a Google-backed satellite company aimed at supporting super-fast broadband connections to Africa and other emerging markets, revealed late last year that it has raised $1.18bn in financing to finally bring the service on line by the first half of 2013.

The company, headquartered in St. John, Jersey, Channel Islands, had originally planned on launching 16 satellites by the end of 2010. But with the global credit crisis squeezing access to funding, O3b’s original plans were postponed as well as revised down. Instead, it plans to launch eight satellites by 2013, with further launches later on.

These will be sent into orbit four at a time on Russian Soyuz rockets operated from Europe’s Guiana Space Center in French Guiana.

The name O3b comes from “the other three billion” a reference to the worldwide population of users who don’t have regular access to the Internet. The company plans on providing broadband to 150 countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Middle East. Founded by Greg Wyler, a technology entrepreneur, the company has previously received funding from Google, satellite operator SES, HSBC, Liberty Global, North Bridge Venture Partners and Allen & Company. Private equity firm Satya Capital and the Development Bank of Southern Africa have signed on as new shareholders bringing the total equity investment to $410mn.

O3b has now secured a $510mn senior debt facility with HSBC, ING, Crédit Agricole and Dexia. HSBC Principal Investments along with a handful of international banks and developmental funding institutions have provided a $115mn Senior Debt Facility and a $145mn Mezzanine Facility. SES, the world’s second-largest satellite operator by revenue, will become the largest minority shareholder for O3b.

According to OB3 CEO Mark Rigolle, “We announced this as being our full financing, and that’s what it is. We will be able to launch our first eight satellites, with all the CAPEX and OPEX that this entails, with interest charges on the debts covered as well. That will bring us to a cash flow generative position, which will then allow us to plough further cash back into the business to grow. Only if we were to decide to accelerate our growth trajectory, would we then decide to add some incremental debt at that point.”

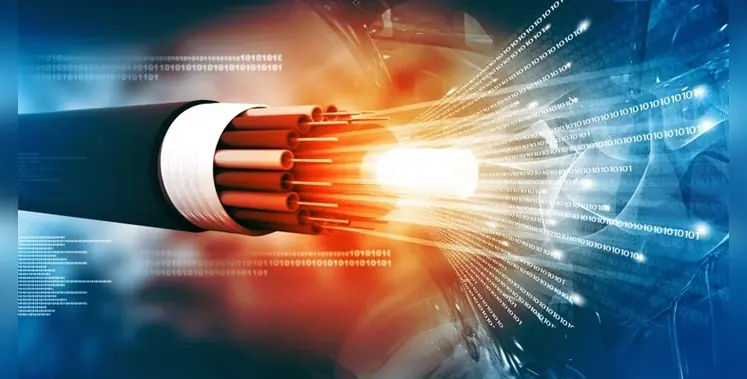

O3b said it has already signed deals worth between $500 and $600mn with companies that want to use the company’s planned network. O3b will primarily serve mobile operators and Internet service providers, providing backhaul for voice and data. The network will consist of the eight Ka-band satellites orbiting at 8,000 km, four times closer than regular geostationary satellites. The proximity of the satellites and their use of the Ka-band will mean better performance and extremely low latency.

The backing of this project in September 2009 by France’s Coface export-credit agency came just two months after mobile satellite services provider Globalstar of California secured $738mn in financing for its second-generation satellite constellation with key Coface support. It is the latest demonstration of Coface’s willingness to take risks on behalf of projects that put French aerospace engineers to work but for which it would otherwise be difficult to raise commercial-bank financing.

However, as Rigolle points out, Coface does not guarantee 100 per cent of the risk, thereby “giving the banks true justification to go through a very thorough credit screening process. The four banks we have on our programme today feel that this is something they would have done on their own balance sheet.”

When questioned on whether another failure would damage the credibility of the industry, Rigolle makes it clear that OB3 is “not geostationary, we’re in mid-earth orbit. There is no direct competitor and no direct comparison in terms of a rival trying to offer a similar service. All these equity investors are very much for-profit operations and they see huge upside potential in this operation. There are DFIs like the ADB who don’t want to lose their money but their primary goal is to get development going in regions of the world where development is still lacking. Having them on board, underscores that we’re going to make a lot of money for our investors.”

KA is certainly in vogue, with Atlantic Systems and Eutelsat about to launch and Inmarsat having placed orders for three satellites already. So why all of a sudden is KA the big game in town? Rigolle’s view is that there is “nothing spectacularly special about any particular frequency band. The uniqueness of KA is that it’s available and not really being used, at least not much. So it’s the next frontier of growth opportunity.”

Rigolle points out that other frequency bands all have their technical and physical characteristics, advantages and disadvantages. “For us KA was a very obvious choice because it enables us to cram the high power we can bring to bear within our beam, considering we are closer to earth than geostationary. We can cram a hell of a lot of bits into our megahertz. It allows us to re-use frequencies. We can offer really big pipes from our neo-orbit. But there’s nothing magical about the frequency band as such. Most of the geo systems I’m aware of are targeted more to the direct-to-consumer market, whereas we are clearly B2B. People who use KA are not necessarily doing the same thing or going after the same thing.”

With geostationary operators, says Rigolle, the more video you can get, the better. “Backhauling is a byproduct almost,” he adds. “That market is being eroded by fibre as fibre penetrates different geographies. So why go after that market? The reason for us to do so is that we believe that for many years to come, there will be an enormous need in many parts of the world for point to point, simply because fibre is not everywhere. If you have a landing point in a landlocked country in Africa or Latin America, that doesn’t help you if you are 100km inland, because you cannot get to the landing point often. So where the reach of fibre is not enough, you will still need satellite gap-fillers to solve that problem.”

O3B sees enormous potential for more distributed networks like mobile networks to have multiple uplink/downlink sites within a footprint or diameter of the beam, which is 600km. According to Rigolle, this means it is possible to cover counties like Pakistan with just a few beams, and immediately roll out a 3G network with very low CAPEX.

“The big advantage is an abundance of bandwidth available at a cost point where geostationary similar cannot compete, and a latency which is comparable to that found in the fibre networks in the areas we serve. In terms of latency we are less than a fourth of the distance from earth compared to geostationary, meaning roughly 120-130 milliseconds.”

A short to medium-length market?

Rigolle admits that spots with very bad DSL or high speed Internet coverage in Europe will dry out very quickly and so the market potential will not be long lived. “But we’re going after more than half the world’s surface, with two thirds of the world’s population living in that area. It is vast. Also another great system we have is the flexibility of the beams, insofar as we can re-point the beams. If we had a beam over Lagos, for example, and Lagos later underwent a fibre roll-out, we could then just point the beam up to Cameroon and cover parts of that region instead. So we can stretch that the potential by being flexible.”